How to Handle Monetary Values in JavaScript

Money is everywhere. Banking apps, e-commerce websites, stock exchange platforms, we interact with money daily. We also increasingly rely on technology to handle ours.

Yet, there’s no consensus around how to programmatically handle monetary values. It’s a prevalent concept of modern societies, yet it’s not a first-class data type in any mainstream language, while things like date and time are. As a result, every piece of software comes up with its own way of handling money, with all the pitfalls that come with it.

Pitfall #1: Money as Number

Your first instinct when you need to represent money might be to use a Number. Money is nothing more than a numeric value, right? Wrong.

The amount part of a monetary value is only relative to another aspect: its currency. There’s no such thing as 10 “money”. It’s 10 dollars, 10 euros, 10 bitcoins… If you want to add two monetary values with different currencies, you need to convert them first. Same if you want to compare them: if all you have is an amount, you can’t make an accurate comparison. Amount and currency can’t go without one another.

Pitfall #2: Floating point math

Most contemporary currencies are either decimal or have no sub-units at all. This means that when money has sub-units, the number of these in a main unit is a power of 10. For example, there are 100 cents in a dollar, being 10 to the power of 2.

Using a decimal system has advantages, but raises a major issue when it comes to programming. Computers use a binary system, so they can’t natively represent decimal numbers. Some languages have come up with their own solutions like the BigDecimal type in Java or the decimal type in C#. JavaScript only has the Number type, which can be used as an integer or a double precision float. Because it’s a binary representation of a base 10 system, you end up with inaccurate results when you try to do math.

0.1 + 0.2 // returns 0.30000000000000004 😧Using floats to store monetary values is a bad idea. As you calculate more values, the imperceptible precision errors lead to larger gaps. This inevitably ends up causing rounding issues.

Pitfall #3: Percentage vs. allocation

Sometimes you need to split money but percentages can’t cut it without adding or losing pennies.

Imagine you need to bill $999.99 with a 50% downpayment. This can be done with some simple math. Half is $499.995, but you can’t split a penny so you’ll likely round the result to $500. Problem is, as you charge the second half, you end up with the same result and charge a penny extra.

You can’t solely rely on percentages or divisions to split money because it’s not divisible to infinity. Gas price may show more than two fraction digits, but it’s only symbolic: you always end up paying a rounded price.

Engineering to the rescue

As you can see, there is much more to money than meets the eye, and it’s more than simple Number data types can take.

Fortunately, software engineer Martin Fowler came up with a solution. In Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture, he describes a pattern for monetary values:

Properties

- amount

- currency

Methods

- math: add, subtract, multiply, allocate

- comparison: equals to, greater than, greater than or equal, lesser than, lesser than or equal.

From this, you can create value objects that fulfill most of your monetary needs.

Money as a data structure

Money behaves differently from a simple number, and thus should be treated differently. The first and most important thing is that it should always be composed of an amount and a currency.

You can do everything from an amount and a currency. You can add monetary amounts together, check if they’re equal or not, format them into whatever you need. This can be done through an object’s methods. In JavaScript, any kind of function that returns an object will do the trick.

Amounts in cents

There are several ways you can solve the floating point issue in JavaScript.

You can use libraries like Decimal.js that will handle your floats as strings. This isn’t a bad solution and even comes handy when you have to handle big numbers. Yet, it comes at the expense of adding a (heavy) dependency, and slower performances.

You can multiply floats into integers before you calculate, then divide them back.

(0.2 * 100 + 0.01 * 100) / 100 // returns 0.21 🎉It’s a fine solution but requires extra calculations either on object construction or on each manipulation. This isn’t necessarily draining on performances, but still more process work than necessary.

A third alternative is to directly store values in cents, relative to the unit. If you need to store 10 cents, you won’t store 0.1, but 10. This allows you to work with integers only, which means safe calculations (until you hit big numbers) and great performances.

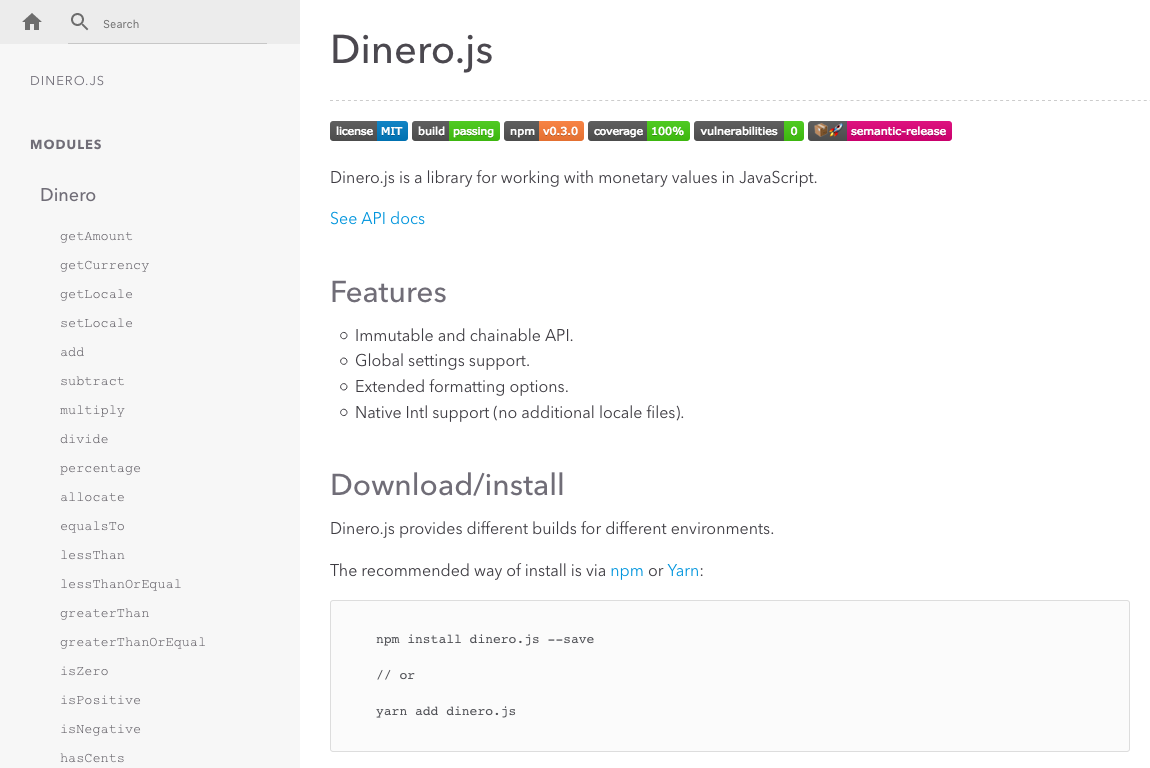

Dinero.js, an immutable library to create, calculate and format monetary values

From these observations, I made a JavaScript library: Dinero.js.

Dinero.js follows Fowler’s pattern and more. It lets you create, calculate and format monetary values in JavaScript. You can do math, parse and format your objects, ask them questions and make your development process easier.

The library was designed to be immutable and chainable. It supports global settings, has extended formatting options and provides native internationalization support.

Why immutable?

An immutable library is safer and more predictable. Mutable operations and reference copies are the sources of many bugs. Opting for immutability avoids them altogether.

With Dinero.js, you can perform calculations without worrying about altering original instances. In the following Vue.js example, price won’t be altered when priceWithTax is called. If the instance was mutable, it would.

const vm = new Vue({

data: {

price: Dinero({ amount: 500 })

},

computed: {

priceWithTax() {

return this.price.add(this.price.percentage(10))

}

}

})Chainability

Good developers strive to make their code more concise and easier to read. When you want to successively perform several operations on a single object, chaining provides an elegant notation and concise syntax.

Dinero({ amount: 500 })

.add(Dinero({ amount: 200 }))

.multiply(4)

.setLocale('fr-FR')

.toFormat() // returns "28,00 US$"Global settings

When you’re handling lots of monetary values, chances are you want some of them to share some attributes. If you’re making a website in German, you’ll likely want to show amounts with the German currency format.

This is where global settings come in handy. Instead of passing them to every instance, you can declare options that will apply to all new objects.

Dinero.globalLocale = 'de-DE'

Dinero({ amount: 500 }).toFormat() // returns "5,00 $"Native Internationalization support

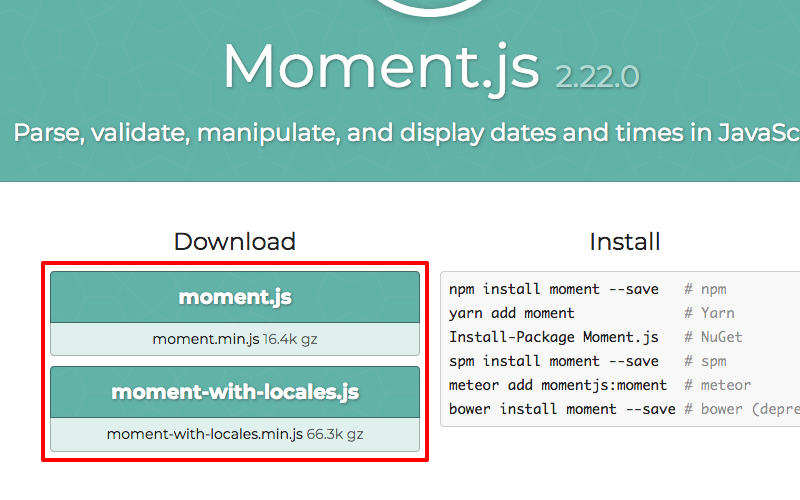

Traditionally, libraries use locale files for internationalization. If you’re exhaustive, they tend to make libraries much heavier.

Moment.js is four times heavier with locale files.

Moment.js is four times heavier with locale files.

Locale files are also hard to maintain. The Internationalization API is native and pretty well supported. Unless you have to work with outdated and/or marginal browsers, toFormat is safe to use.

Formatting

An object is great to store data, but not so helpful when it comes to displaying it. Dinero.js comes with various formatting methods, including toFormat. It provides intuitive and concise syntactic sugar over Number.prototype.toLocaleString. Pair it with setLocale and you’ll be able to display any Dinero object into the proper format, in any language. This is particularly helpful for multi-lingual e-commerce websites.

What’s next?

Fowler’s money pattern is widely recognized as a great solution. It has inspired many implementations in many languages. If you’re into DIY, I recommend it and the observations from this article as a starting point. Or you can pick Dinero.js: a modern, reliable, fully tested solution that already works. Have fun!

Any questions about Dinero.js? Or on how to make your own money data structure? Let’s chat on Twitter!